At about forty years of age, Margery Kempe, married twenty years and mother to fourteen children, took a vow of chastity with the consent of her husband and the Church and was free to go wherever she wished to go. She became - for the rest of her long life - a pilgrim. Ever on the move, first to Jerusalem and the Holy Land, then Rome and onwards to Spain and Prussia, her reputation as a pilgrim who felt bodily and psychologically the sorrows of her faith became well known across Europe and England. In her autobiography, itself an achievement for a late Medieval woman of the 1400s, (who could neither read nor write), she describes her manner of distress at the sight of Christ on the cross as “a gift of tears.” Some of those who witnessed her hysterics and fits of crying accepted her behavior as overwrought and extreme but fitting for a highly devoted Christian. She had many supporters. Others, however, considered her an erratic, overly dramatic, even heretical, performer. She seemed to have had many more detractors. She was arrested numerous times, integrated for heresy while imprisoned, but never convicted.

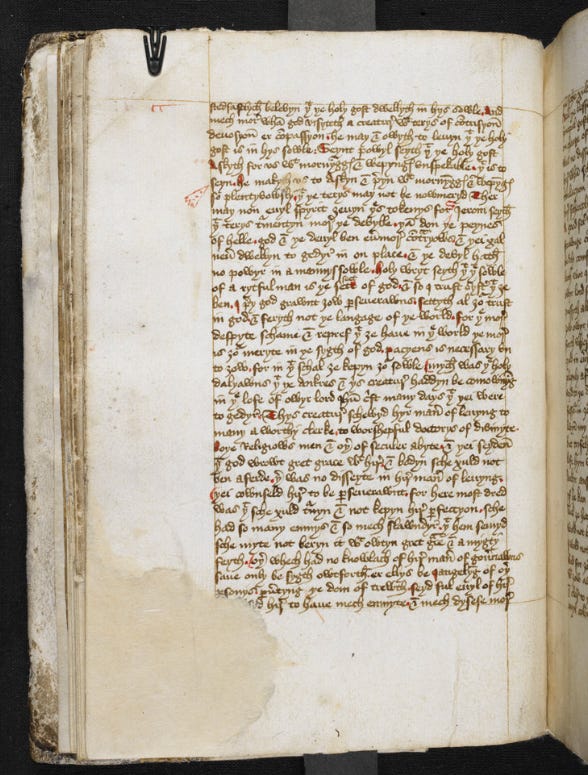

As a Christian mystic, named so after her death a few years since her last voyage in 1438, Margery Kempe and her amazing autobiography, dictated to two scribes when she was quite old, have provided us with an extraordinary history of a woman of and outside of her times. Hers was the first autobiography by an English woman and though she was known to the history of Christian women mystics as an anchorite (she was not!) who lived in a cell in Lynn, Lancashire, her story wasn’t fully known until 1934 when Col. William Butler-Bowdon discovered The Book of Margery Kemp (1438) in his family’s Lancashire home library.

Colonel Butler-Bowdon’s discovery was authenticated by a series of scholars that confirmed the manuscript had been created as a copy of the original, long gone now, produced by an assistant of the scribe who took dictation from Kempe directly. “Our family has always been devout Catholic in the Lancashire area neighbor to the Capuchin abbey that originally housed an impressive library of manuscripts,” said Butler-Bowdon in a 1939 interview. “It was probably given to our family with other important books for safekeeping during the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1538.” (Atkinson, pg 21)

I’d like to introduce Margery Kempe as one woman wandering, a term reserved for women pilgrims who took to the long roads, a-sauntering to last a lifetime. I’m taking a deep dive over several weeks to tell her story and to try to relate her to women wanderers of the 20th and 21st centuries.

I am using the historic meaning of the word saincte terre as one who travels to and on holy land to describe these women, Kempe especially. During the High (or Late) Middle Ages when Kempe lived sauntering was taken up by many women wandering, sauntrer a’aventurers, who took great risks with their many notable springtime strolls, walks, and expeditions to leave household and husbands, to break with society (mostly men) that viewed them with suspicion and scorn. Crazy women walkers. Idlers and vagabonds. Like you and I.

Notes:

Atkinson, Clarissa (1983) Mystic and Pilgrim: The Book and World of Margery Kempe. Cornell University Press.

Can't wait to find out more about our "sister", Margery!